This will hopefully be the first of a series of posts based on a book that has substantially influenced me over the last several years, The Elements of Statistical Learning (EoSL) by Hastie, Tibshirani, and Friedman (I went and got a degree in statistics essentially for the purposes of better understanding this book). Best of all, the pdf version of EoSL is now available free of charge at the book’s website, along with data, code, errata, and more.

This post will demonstrate the use of Linear Discriminant Analysis and Quadratric Discriminant Analysis for classification, as described in chapter 4, “Linear Methods for Classification”, of EoSL.

I will implement the classifiers in Clojure and Incanter, and use the same data set as EoSL to train and test them. The data has 11 different classes, each representing a vowel sound, and 10 predictors, each representing processed audio information captured from eight male and seven female speakers. Details of the data are available here. The data is partitioned into a training set and a test set.

The task is to classify each of the N observations as one of the (K=11) vowel sounds using the (p=10) predictors. I will do this using a Bayes classifier built from both linear- and quadratic-discriminant functions. The Bayes classifier works by estimating the probability that an observation, x, belongs to each class, k, and then selects the class with the highest probability. Appropriately, Bayes rule is used to calculate the conditional probability , or posterior probability, for each class.

(eq 4.7)

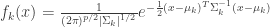

Where,  is the prior probability of class k. If we model each class density as multivariate-normal, then

is the prior probability of class k. If we model each class density as multivariate-normal, then  , where

, where

(eq 4.8)

and the posterior probability becomes

(eq 4.7)

Since the denominator is the same for each class, we can ignore it, and if we take the log of the numerator and ignore the constant,  , in the density function, we end up with the quadratic discriminant function:

, in the density function, we end up with the quadratic discriminant function:

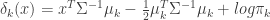

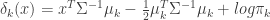

(eq 4.12)

If we further assume that the covariance matrices,  are equal for each cluster, then more terms cancel out and we end up with the linear discriminant function,

are equal for each cluster, then more terms cancel out and we end up with the linear discriminant function,

(eq 4.10)

Classification is then performed with these discriminant functions using the following decision rule:

(eq 4.10a)

In other words, select the class, k, with the highest score for each observation.

Implementing the LDA Classifier

Start by loading the necessary Incanter libraries and the data sets from the EoSL website:

(use '(incanter core stats charts io))

(def training (to-matrix

(read-dataset "http://bit.ly/464h4h"

:header true)))

(def testing (to-matrix

(read-dataset "http://bit.ly/1btCei"

:header true)))

Define the fixed parameters:

(def K 11)

(def p 10)

(def N (nrow training))

(def group-counts (map nrow (group-by training 1)))

Since we don’t know the parameters of the multivariate-normal distributions used to model each cluster, we need to estimate them with the training data. First, estimate the prior probabilities for each cluster

(eq 4.10b)

where  is the number of observations in class k, and

is the number of observations in class k, and  is the total number of observations.

is the total number of observations.

(def prior-probs (div group-counts N))

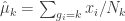

Next, estimate the centroids for each cluster

(eq 4.10c)

(def cluster-centroids

(matrix

(for [x_k (group-by training 1 :cols (range 2 12))]

(map mean (trans x_k)))))

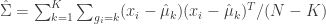

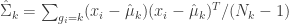

Finally, estimate the covariance matrix to be used for all clusters,

(eq 4.10d)

(def cluster-cov-mat

(let [groups (group-by training 1 :cols (range 2 12))]

(reduce plus

(map (fn [group centroid n]

(reduce plus

(map #(div

(mmult (trans (minus % centroid))

(minus % centroid))

(- N K))

group)))

groups cluster-centroids group-counts))))

and its inverse:

(def inv-cluster-cov-mat (solve cluster-cov-mat))

With the parameters estimated, now define the linear discriminant function based on equation 4.10 from EoSL:

(eq 4.10)

(defn ldf [x Sigma-inv mu_k pi_k]

(+ (mmult x Sigma-inv (trans mu_k))

(- (mult 1/2 (mmult mu_k Sigma-inv (trans mu_k))))

(log pi_k)))

Differences in the equation, as implemented in the code, and equation 4.10 are because most of the arguments to the ldf function above are row vectors, instead of the column vectors used in eq 4.10.

Next, define a function that returns a matrix of linear discriminate scores, where rows are observations and columns are classes,

(defn calculate-scores

([data inv-cov-mat centroids priors]

(matrix

(pmap (fn [row]

(pmap (partial ldf row inv-cov-mat)

centroids

priors))

(sel data :cols (range 2 12))))))

and calculate the scores for the training data

(def training-lda-scores

(calculate-scores training

inv-cluster-cov-mat

cluster-centroids

prior-probs))

Now, create a function that returns the index (i.e. class) with the maximum score for a given row (i.e. observation) of the scoring matrix,

(defn max-index

([x]

(let [max-x (reduce max x)

n (length x)]

(loop [i 0]

(if (= (nth x i) max-x)

i

(recur (inc i)))))))

We can get a vector of the predicted class for every observation in the training set with the following line of code:

(map max-index training-lda-scores)

To determine the error rate of the classifier, create the following function,

(defn error-rate [data scores]

(/ (sum (map #(if (= %1 %2) 0 1)

(sel data :cols 1)

(plus 1 (map max-index scores))))

(nrow data)))

and apply it to the score matrix for the training data,

(error-rate training training-lda-scores)

which returns an error rate of 0.316.

Now let’s see how the classifier performs on the test data. Start by calculating the linear discriminant score matrix,

(def testing-lda-scores

(calculate-scores testing

inv-cluster-cov-mat

cluster-centroids

prior-probs))

and then calculate the error-rate,

(error-rate testing testing-lda-scores)

which is 0.556. As expected the error rate is higher on the test data than the training data.

Implementing the QDA Classifier

In order to use QDA to classify the data, we need to estimate a unique covariance matrix for each of the K classes, and write the quadratic discriminant function.

First, estimate the covariance matrices,

(eq 4.10e)

(def cluster-cov-mats

(let [groups (group-by training 1 :cols (range 2 12))]

(map (fn [group centroid n]

(reduce plus

(map #(div

(mmult (trans (minus % centroid))

(minus % centroid))

(dec n))

group)))

groups cluster-centroids group-counts)))

and their inverses.

(def inv-cluster-cov-mats (map solve cluster-cov-mats))

Next, create a function that implements the quadratic discriminant function:

(eq 4.12)

(defn qdf [x Sigma_k Sigma-inv_k mu_k pi_k]

(+ (- (mult 1/2 (log (det Sigma_k))))

(- (mult 1/2 (mmult (minus x mu_k)

Sigma-inv_k

(trans (minus x mu_k)))))

(log pi_k)))

Then calculate the quadratic discriminant score matrix and error rates for the training and test data, which are 0.0113 and 0.528 respectively. Notice that the error rate is substantially lower on the training data than it was with LDA (0.316), but the error rate on the test data is not much better than that achieved by LDA (0.556).

Improving Performance

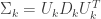

Hastie, Tibshirani, and Friedman suggested performance of the calculations can be improved by first performing an Eigenvalue decomposition of the covariance matrices.

where  is the matrix of eigenvectors, and

is the matrix of eigenvectors, and  is a diagonal matrix of positive eigenvalues

is a diagonal matrix of positive eigenvalues  .

.

(def Sigma-decomp

(map decomp-eigenvalue cluster-cov-matrices ))

(def D (map #(diag (:values %)) Sigma-decomp))

(def U (map #(:vectors %) Sigma-decomp))

Making the following substitutions to  ,

,

(a) ![(x-\hat\mu_k)^T\hat\Sigma_k^{-1}(x-\hat\mu_k)=[U_k^T(x-\hat\mu_k)]^TD_k^{-1}[U_k^T(x-\hat\mu_k)]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%28x-%5Chat%5Cmu_k%29%5ET%5Chat%5CSigma_k%5E%7B-1%7D%28x-%5Chat%5Cmu_k%29%3D%5BU_k%5ET%28x-%5Chat%5Cmu_k%29%5D%5ETD_k%5E%7B-1%7D%5BU_k%5ET%28x-%5Chat%5Cmu_k%29%5D+&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002)

(b)

results in the following quadratic discriminant function:

(eq 4.12) ![\delta_{k}(x)=-\frac{1}{2}\sum_l log(d_{kl})-\frac{1}{2}[U_k^T(x-\hat\mu_k)]^TD_k^{-1}[U_k^T(x-\hat\mu_k)]+log\pi_k](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cdelta_%7Bk%7D%28x%29%3D-%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B2%7D%5Csum_l+log%28d_%7Bkl%7D%29-%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B2%7D%5BU_k%5ET%28x-%5Chat%5Cmu_k%29%5D%5ETD_k%5E%7B-1%7D%5BU_k%5ET%28x-%5Chat%5Cmu_k%29%5D%2Blog%5Cpi_k+&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002)

(defn qdf [x D_k U_k mu_k pi_k]

(+ (- (mult 1/2 (sum (map log (diag D_k)))))

(- (mult 1/2

(mmult (trans (mmult (trans U_k)

(trans (minus x mu_k))))

(solve D_k)

(mmult (trans U_k)

(trans (minus x mu_k))))))

(log pi_k)))

This version of the quadratic discriminant function is a bit faster than the previous version, while producing the exact same results. The performance improvement should be greater with larger data sets.

The complete code for this post can be found here.